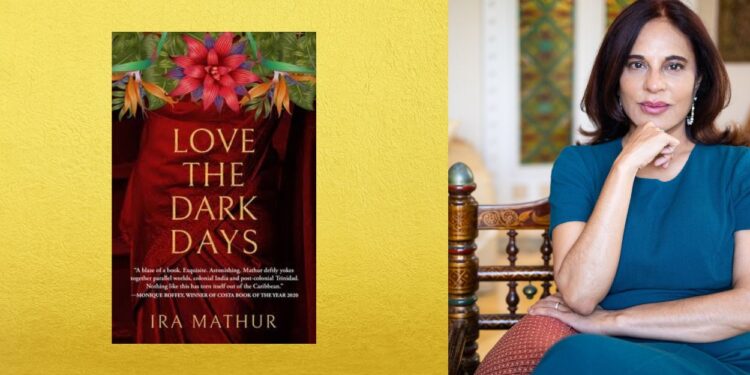

Ira Mathur, the Indian-born Trinidadian journalist, columnist, and award-winning author of Love The Dark Days, has built her career on amplifying the voices of those too often unheard. With family roots stretching from the Nawab of Bhopal to her grandmother Shahnur Jehan and great-grandfather Abdul Majid Khan, Mathur’s own sense of being “an outsider”—as she describes herself, “Half Hindu and Half Musalman”—has deeply shaped her worldview and her writing.

Also, she is columnist for the Sunday Guardian (Trinidad & Tobago) and has freelanced for The Guardian (UK), BBC, and The Irish Times. Academically, she holds degrees in Literature and Philosophy, Law (LLB from the University of London), and a Master’s in International Journalism from City University, London.

The following conversation explores the creation and ethos of the Women section— on her site –Ira’s Room (irasroom.org), a dedicated space for amplifying women’s stories often silenced or overlooked. Through deeply personal reflections and journalistic insights, the writer speaks on memory, violence, resilience, and the responsibilities of telling women’s stories with honesty and care.

Ira Mathur on Family, the Nawab of Bhopal, and Why She Created the ‘Women’ Section on Ira’s Room

1. Inspiration Behind the Women Section

I created the Women section to give voice to the many stories of women that too often go unheard. In Trinidad & Tobago, despite legislative progress—such as the Domestic Violence Act—and strides in education, women still suffer routine violence and marginalisation. Nearly forty to fifty women are murdered each year, often after enduring rape, beatings, or harassment that was previously reported and ignored. These grim realities compelled me to carve out a dedicated space.

In practice, the section chronicles both individual and collective experience. It brings into focus the ways women—mothers, grandmothers, daughters—are burdened as primary caregivers, often without adequate support. My own family history deeply informs this work. My grandmother, Shahnur Jehan Begum, a brilliant pianist, won a scholarship to study in Vienna, but was married off young and never fulfilled her dreams. Her story—like so many women’s—underscored that education and self-realisation are not luxuries, but necessities. Likewise, my maternal grandmother, Kamla, was denied education and the right to vote, yet she raised her sons to be feminists and insisted that her daughters—and granddaughters—be given every opportunity.

These multi-generational stories revealed how structural gender barriers cut across time, class, and geography. They pushed me to document what is often invisible. There wasn’t a single dramatic turning point, but rather an accumulation: the stories women shared in confidence, the police reports and death notices, the silences in family homes. The Womensection exists to connect these fragments—to show that individual pain and private endurance belong to a much larger, political story. It’s a space where the personal meets the public; where memory, violence, and resistance are not just anecdotal, but central to understanding the societies we live in.

2. Balancing Intimate Storytelling with Journalism

Navigating the line between personal narrative and journalistic rigour is a constant act of calibration. On the one hand, I am committed to the demands of journalism—facts, verification, context. On the other, I allow my writing to remain intimate, vulnerable, and emotionally alert. That duality is where much of my work lives.

People open their hearts to journalists with the hope that their stories will not be reduced to spectacle or statistics, but will be heard in full complexity. That trust demands care. It means that when I write about domestic violence or institutional neglect, I am not just reporting—I am bearing witness. I must be honest, but not exploitative. I must write clearly, but not coldly. Often, it’s about tone: how you frame the story, how much you allow silence or pain to speak without interruption.

In my memoir, Love The Dark Days, I wrote about my own family’s entanglement with empire, migration, and loss. It was personal, but not solipsistic. The narrative was always reaching outward—towards race, gender, history. That same principle guides the Women section. The personal detail is not there for decoration. It is evidence. It illuminates the political.

Writing in this way means allowing for contradiction and ambiguity. A woman may recount a violent episode and still express loyalty to her abuser. A mother may pass on both resilience and trauma. The role of the writer is not to resolve these tensions, but to document them honestly. My aim is always to expand empathy and understanding without abandoning clarity. That is the quiet but radical act journalism still makes possible.

4. Many of your essays reflect on silence and the unspoken. How do you approach writing about trauma without sensationalising it?

I try to treat each story with honesty and care, bearing witness rather than exploiting pain. My first responsibility is to the truth—but also to the people who entrust me with their trauma. In practice, I let survivors speak in their own words and focus on concrete details, so the story remains about them, not about drama.

When I write about women murdered in domestic violence, for instance, I’ve noticed that news reports often reduce victims to mere fragments—where they were last seen, how they died—while the rest of their lives vanish. In my work, I try to recover those missing pieces and write with dignity, not spectacle. That’s how I honour both the story and the storyteller.

5. The pieces resonate with generational pain and resistance. How do you see your work in conversation with other women’s voices—past and present?

I see my work as part of an ongoing conversation across generations. Love the Dark Days weaves together the stories of my grandmother, my mother and myself, tracing how patterns of hurt—and strength—are passed down. Mothers rarely intend to hurt their daughters, but they often do, because of what they’ve inherited themselves.

My daughter helped me see this. I raised her to question silence, to name what was passed down unconsciously, and in doing so, she helped me confront my own blind spots. Critics have called the book a Caribbean feminist memoir because it reveals how colonial legacies and patriarchy still harm women, then and now. Writing in this way allows me to speak alongside other women—to honour their endurance and amplify their voices.

6. You mention institutional neglect and erasure. Do you think journalism today is doing enough to centre marginalised women’s narratives?

Not nearly enough. Stories of violence and injustice against women are too often sidelined. In some newsrooms, brutality is dismissed as “family business,” and victims are reduced to headlines, their lives erased.

We have laws against domestic violence, but without the will or systems to enforce them, they’re little more than words on paper. Journalism has a duty to fill that gap—to report with rigour, yes, but also with humanity. I see progress when editors dedicate space to these stories, but it requires consistent effort. We must shine light into the places society wants to keep dark.

7. As a journalist and writer dealing with sensitive subjects, how do you balance emotional responsibility with editorial distance?

It’s a constant calibration. I remain committed to the demands of journalism—verifying facts, providing context, writing clearly—while never losing my humanity. People entrust me with their most painful memories, and I take that responsibility seriously.

Tone is crucial. I allow silence to speak. I don’t embellish or interrupt suffering with analysis. Instead, I try to let the story breathe. I aim to write honestly, without being cold; emotionally alert, without becoming indulgent. That tension—between intimacy and rigour—is where my best work lives.

8. When writing about others’ pain, especially women who’ve faced violence or systemic neglect, how do you ensure you’re telling their story and not just framing it?

I start by listening—really listening. I ask myself constantly: whose story is this? Am I bearing witness or taking over?

I let women speak for themselves as much as possible. I focus on the details of their lives: what they loved, what they hoped for, what was left unsaid. The story must reflect their reality, not my agenda. As a journalist, I see myself as a vessel for truth. The best reporting gives voice to those who are usually unheard. That means writing with humility, not authority. I don’t presume to explain anyone’s life—only to honour it.

9. What reactions have moved you most—either from readers, institutions, or the women you’ve written about?

I’ve been grateful for critical recognition—winning the OCM Bocas Prize for non-fiction and being listed among the Guardian’s best memoirs of the year—but what moves me most are the private responses.

When women write to say, “You put into words what I’ve lived,” or that something I wrote made them feel less alone, that’s when I know the work matters. One reader said a single paragraph in Love the Dark Days gave her the courage to speak to a sibling after twenty years . Another made her confront the love that also came with harsh parents. No award can equal that kind of connection.

10. How do you envision readers engaging with the Women section? Is it about empathy, activism, documentation—or something else?

All of those, ideally. Empathy is the starting point. These are not abstract issues—they’re real people’s lives. I want readers to feel the weight of each story, to care deeply, and to see the patterns behind the pain.

But it’s also about documentation. These essays create a kind of unofficial archive of Caribbean women’s lives—what we endure, what we resist, how we love. And yes, it’s about activism too. My hope is that some readers will be moved to act: to support shelters, to vote differently, to listen more closely. Ultimately, I want the section to hold a mirror up to society and say: this matters. Don’t look away.

11. What stories or themes are you hoping to explore next through Ira’s Room?

Another forthcoming book gathers essays on India. And I’m planning a third based on letters between my parents in pre-Independence India, compared to their lives in Trinidad as my father was dying. These are all, in different ways, stories about memory, migration, and how we carry and release love.

12. If a young journalist came to you, wanting to write honestly about gender, class, and injustice, what advice would you give them?

Be fearless. Stay rooted in the truth. The power of journalism lies in telling uncomfortable stories that others might prefer to silence.

Be prepared to be challenged. The world often resists truth-tellers—especially women of colour writing about injustice. But remain rigorous: verify every fact, interrogate your own biases, and never condescend to your subjects.

Most importantly, listen. People share their pain with us in the hope it will be treated with respect. Your job is not just to report what happened, but to reveal why it matters. That takes empathy, discipline, and above all, courage. If you can do that, you’ll be serving something far greater than yourself.